Maybe Our Diversity Problem Is Really a Curiosity Problem

When we are curious, we are better able to bridge the gap between our own experiences and other people's experiences, and we see the world through an expanded lens.

Growing up in the suburbs in the eighties was a very homogeneous experience for me. Of course, I didn't know that then, but looking back it is plain as day. For example, from the time I entered kindergarten to the time I left high school, I can only remember one Black student with whom I had any interaction. His name was Langston, and while it would be a stretch to say he was my friend, I do remember playing with him from time to time in third and fourth grade.

Recently, I tried to look him up online. I couldn't find him on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, or other social media platforms, and there was nothing in the news about him. I did find someone named Langston with his last name on one of those public online directories. His age was listed as the same as mine, and this person named Langston still lives in my (our) hometown.

Could it be him? I don't know, but it probably is, right? I mean, how many Langstons with his last name and the same age as me could be living in the hometown where we grew up? I wrote down his number.

And then. . .

And then what? Am I going to call him? What would I say? "Hey, Langston, this is Jared Karol. You might not remember me, but we used to play together at Madison Elementary School back in the early eighties. You were the only Black person I knew, and now I do diversity work, and I thought it'd be cool to catch up."

Awkward.

In my search for Langston, an article came up from a couple years ago about the death of a doctor in his seventies with the same last name. The doctor was a Black family practitioner, and the article talked about all the good deeds he did for his patients, most of whom came from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds.

And, the article went on to explain, he always took the time to listen to his patients' stories, eschewing efficiency for personal touch. Even when his patients had to sit in the waiting room past their appointment time, it was okay because they knew they would get quality time with the doctor. Furthermore, as the senior doctor in the practice, he always took the time to mentor young doctors – especially young African-American female doctors – because he knew how difficult it was for them to break into the medical field.

Wow! Sounds like an awesome guy. Was that Langston's dad? The ages match up, the hometown matches up. How could it not be? Was Langston named after Langston Hughes, the Harlem Renaissance poet, a tireless advocate for the advancement of Black people? Judging by the write up of this doctor, it makes sense that a highly intelligent, socially conscious man who used his power and privilege to help the underserved would want the namesake of a famous Black poet with the same values ascribed to his son.

The article was rather long, and just as I was about to click away before the last few paragraphs, I read that the doctor was survived by his wife and five children, one of whom was named. . . Langston! It is him. I've found my guy. I have his phone number, so I should just call him, right? Maybe I will, maybe I won't. I don't know yet. I think I will, but. . . I'll let you know.

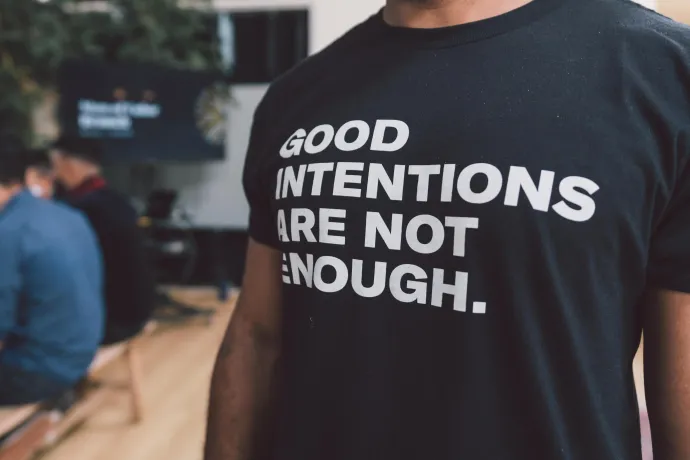

My lack of curiosity about those who I perceived to be "not like me" led to missed opportunities to connect with people from a wide range of backgrounds.

This story is just one of dozens of examples I could have shared that illustrate how my lack of curiosity about those who I perceived to be "not like me" led to missed opportunities to connect with people from a wide range of backgrounds. The result was that I grew up with a very limited perspective of the world and what I considered to be within the range of "normal." For decades, my intellectual and emotional growth was stunted.

It was not until well into my twenties when I began to branch out of my safe, homogeneous circles and meet people with lived experiences vastly different than my own. This is when I began to experience growth and when I began to value the freshness and uncertainty of new friendships with people who were not cisgender, white, straight males like me. This is when I began to value and cherish any and all opportunities to learn about myself and others, and that I began to step into a fuller, more authentic version of myself. This is when I began to find belonging. This is when I began to thrive.

And it all began by being curious.

In elementary school, I was never curious about Langston. After all, my logic went, Langston was Black, and I was white. End of discussion. Similarly, I was never curious about my dad's homosexuality when he told me John was his boyfriend when I was fourteen. After all, my dad was gay, and I was straight. End of discussion. In college, I was never curious about the experiences of women, people from the transgender community, people with disabilities, people who are poor – or, really, anybody who did not fit into my narrow view of "normal." You can see the trend.

In sum, if you weren't more or less like me – with a demographic and psychological profile that made me feel comfortable and safe – it was unlikely that we would be buddies.

But when I began to be curious, I realized all the possibilities that were available to me. I noticed that if I took the time to be interested on purpose in other people's lives, I was able to add value to my life. When I took the time to read, listen, observe, and engage with people not like me, I began to see the vast dynamism of the human condition. By intentionally putting myself into new and unfamiliar situations I began to see the common humanity that we all share. And I loved it. I wanted more of it. I was determined to make up for lost time.

When I began to be curious about other people, my indifference turned into empathy; my disregard changed to compassion; and my preference for disengagement evolved into a strong desire to deeply connect with as many people as I could.

When I began to be curious, I realized all the possibilities that were available to me. I noticed that if I took the time to be interested on purpose in other people's lives, I was able to add value to my life.

So, no, I never had a diversity problem. I had a curiosity problem. I had an apathy problem. A problem of disinterest, inattention, negligence. These are problems I see far too often in our society, our organizations, our communities. You see them too, yes?

So I challenge you to work on solving the curiosity problem by. . . well, by being curious.

Who are you curious about? What person from a perceived different background could you intentionally engage with today, tomorrow, the next day – every day? Could you invite them to lunch or coffee? Could you share something personal about yourself? Could you show genuine interest in them, their hobbies, their backgrounds? Could you find common ground across differences? Could you make new friends? Could you make someone feel appreciated and welcomed? Could you invite and include someone into your circle?

When I began to be curious about other people, my indifference turned into empathy; my disregard changed to compassion; and my preference for disengagement evolved into a strong desire to deeply connect with as many people as I could.

The answer to all these questions is, "Yes, you can." Try it. Try being curious. See what happens. Notice how your relationships change, how your outlook on life improves, how other people feel when they're around you. Notice your growth. Notice the impact you're making on the world. Notice all the beautiful new relationships you develop. Notice. . .

I'd write more, but I'm going to go call Langston. I'm curious to see what he's been up to the last 35 years.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.