8 in 10 Websites leak your search terms

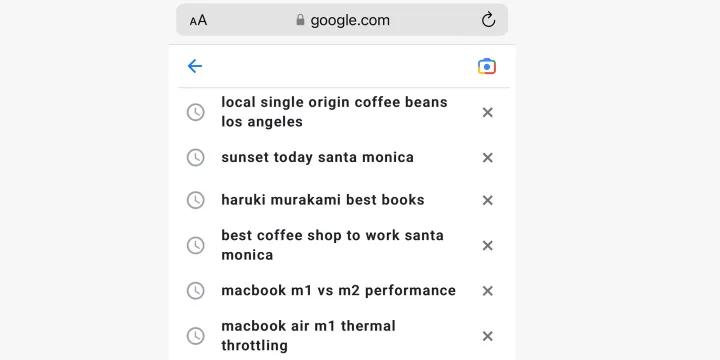

Would you show your close friends your recent search history right now? Does that thought make you nervous? Here’s mine from this morning.

You can tell a lot about me from just these six searches: I live in Santa Monica, I’m thinking about buying a new laptop, I love coffee, and I’m a fan of Murakami books. Even relatively benign searches can paint a vivid picture.

For example, in 2012 Target used its users’ shopping habits to determine which users might be pregnant to sell maternity-related products more efficiently. By doing this, Target inadvertently outed a teenage girl’s pregnancy to her father before she herself was even aware she was pregnant.

Everyone knows by now that Google takes these searches and sells them to advertisers, so they can target you with relevant ads – laptop ads, coffee ads, and ads for niche books by Japanese authors. So what do you do if you want to look up something but don’t want the world to know – perhaps a medical condition or some other private information? One thing you can try is using a site’s search function directly.

Instant privacy, correct? Not so. Our recent research shows these searches are not nearly as private as we might have hoped.

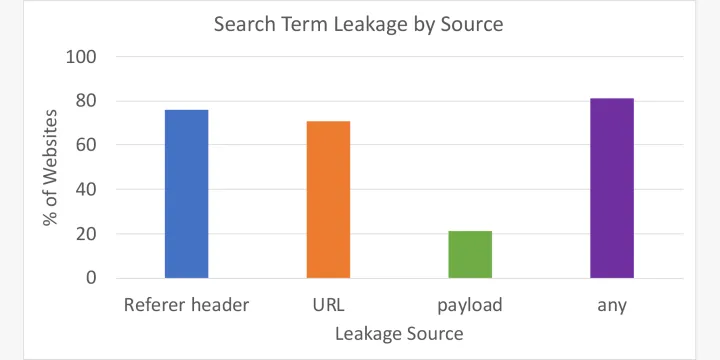

Our work, which we presented at the Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium, showed that 81% of top websites leak search terms to third parties, often advertisers.

These websites range across all imaginable categories — adult, shopping, travel, and even health. The search terms collected by these websites might include sexual preferences and gender identity, purchasing habits, and medical information.

How we zeroed in on leaked search terms

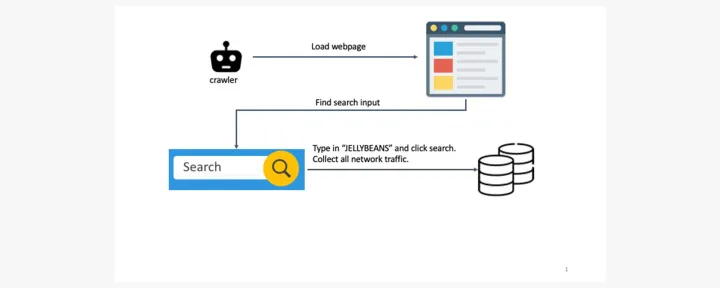

To study how widespread this phenomenon was, we developed an instrumented, headless crawler based on the Chrome browser. It used the internal site search feature of the top 1 million websites to execute searches and captured all web traffic after the search to see where our search terms were sent. We searched for something specific – "jellybeans" – to make sure we could easily find our search terms in the network traffic.

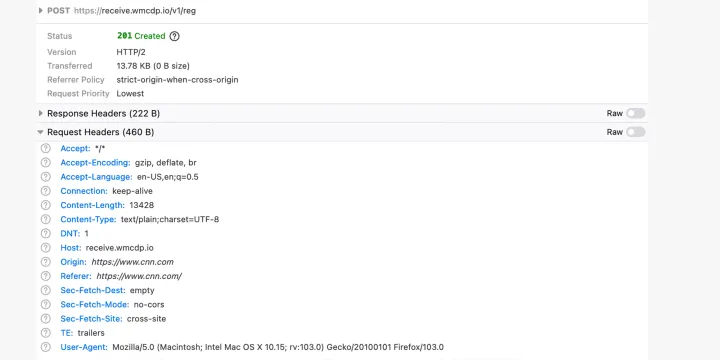

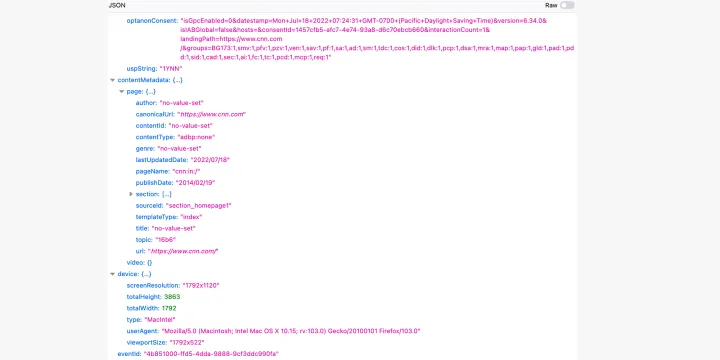

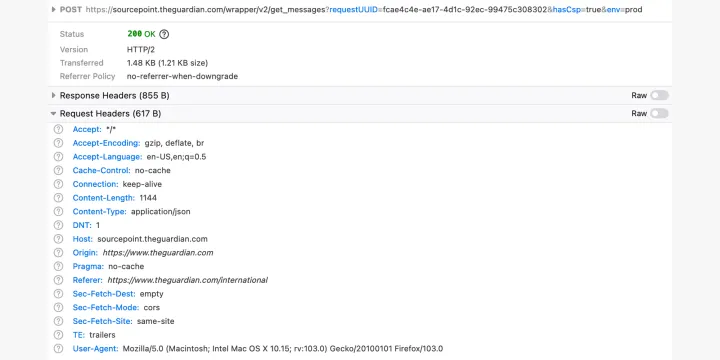

A typical HTTP network request is composed of three parts: the URL, the Request Header, and the payload. The URL is what you see in the address bar. The HTTP Request Header is metadata automatically sent by the browser (see below). The payload is additional data requested by a script or form and might include more detailed tracking information such as a browser fingerprint or clickstream data.

In our study, we looked for “jellybeans” in all three parts of network requests: the Referer Request Header, the URL, and the payload. The Referer header refers to the website that sent the request (see figure 2) but can sometimes contain additional information (see figure 3).

Our headless browser overcame numerous obstacles when crawling the modern web, including dealing with interstitials (think invitations to sign up for a website’s newsletter), as well as finding which inputs on a website actually corresponded to search fields, hidden search fields, and other challenges.

Results

Of the top websites which have internal site search, we observed 81.3% of these websites leaking search terms in some form to third parties: 75.8% of websites via the Referer header, 71% of websites via the URL, and 21.2% of websites via the payload. Often, websites would leak search terms via more than one vector. This shows that most websites, more than eight in ten, leak your search terms.

You can consider these numbers a lower bound, since we looked for the “jellybeans” search string in only three specific locations. We found that, for example, many payloads were obfuscated to avoid inspection by our tools. Therefore, the real numbers for the payload are likely higher.

Privacy Policies

Given our findings, we were curious if websites informed their users that their search terms were often sent to third party websites. Since the passage of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) law in Europe and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in California, many websites now include a privacy policy. While users tend not to read these documents, we wondered whether, if a user did read it, they could learn about how websites treat their search terms.

To this end, we also used our crawler to find privacy policies on the top 1 million websites. We then built an artificial intelligence to read these privacy policies and look for any sections mentioning search terms. We found that only 13% of privacy policies mentioned the handling of user search terms explicitly, a worryingly small percentage. However, 75% of privacy policies referred to the sharing of “user information” with third parties (which may include search terms) using generic wording. We think it’s unlikely that ordinary users can be well-informed on the treatment of their private data based on the wording of these privacy policies.

Mitigations

Unfortunately, websites hold most of the power when it comes to sharing your search terms with third parties. However, there are two things you can do to improve your privacy. First, modern browsers such as the most recent versions of Firefox and Chrome improve user privacy by blocking certain types of privacy leakage in the Referer header. Therefore, using them can provide a privacy advantage.

Second, the Norton AntiTrack product, as well as other tracker-blocking and ad-blocking browser extensions, helps by blocking third party trackers from loading on a webpage. These can have a strong positive effect on your privacy when browsing the modern web.

Editorial note: Our articles provide educational information for you. NortonLifeLock offerings may not cover or protect against every type of crime, fraud, or threat we write about. Our goal is to increase awareness about cyber safety. Please review complete Terms during enrollment or setup. Remember that no one can prevent all identity theft or cybercrime, and that LifeLock does not monitor all transactions at all businesses.

Copyright © 2022 NortonLifeLock Inc. All rights reserved. NortonLifeLock, the NortonLifeLock Logo, the Checkmark Logo, Norton, LifeLock, and the LockMan Logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of NortonLifeLock Inc. or its affiliates in the United States and other countries. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners.